The Trio Hall

Video installation, timebased art, performance and feature film, 2023

What you are seeing is a “cinematic exhibition” or “exhibition cinema”, or it can also be thought of as a place of audiovisual production, where members of the audience can experience a process that entails drawing the storyboard, production meeting, audition, rehearsal, martial arts training, choreography, musical arrangement, and even being on site at the filming location. Finally, a political comedy packed with thorny issues and hellish gags will be produced by the end of the exhibition. This entire experience marks an interim conclusion for my “Re-shooting” series, which asks: Why don’t we tackle chauvinism, colonization, the Cold War, popular culture, mass media, and any pressing crises and dilemmas all at once? This proposal reflects the current new Cold War and extreme politics, and under such circumstances, what kind of humorous narratives can this East Asian island nation of ours come up with? The narratives conjured will then be widely circulated and passed down, as we exclaim to the world and also at ourselves: What the hell is going on?

The Space warriors and the Digigrave

Video installation, website and Minecraft, 2023

In East Asia, during the last decade of the Cold War from 1984 to 1987, CTS, one of Taiwan’s only three official TV stations at that time, produced and broadcasted a very rare and weird sci-fi series, Space Warriors. It was basically copied from the Japanese series Super Sentai in late 1970s with modifications. At the same time, it also referenced the Gavan, the follow-up series of Super Sentai, and was mixed with some local elements. CTS eventually discontinued the series due to low ratings, inconsistent production quality, overt criticism from parents, and the import of the Japanese original on VHS and satellite television. Unfortunately, the sci-fi did not open the people’s imaginative thoughts about the universe and the world, but rather, the series, combined with illogical fantasy and Chinese Folktales and even martial arts elements, subtly implied nationalism, Confucianism, patriarchy, and other values, which was a very strange and unique experience during the martial law period.

Digigrave and the new Space Warriors are fraternal twins, respectively assembling various escaping methods on the Internet, books and physical surfaces. They invite people to revisit the collective experience of the Taiwanese sci-fi genre. Based on my personal childhood memories of martial law during the production and broadcast of Space Warriors, the new Space Warriors will once again use sci-fi as a lever, but it will no longer serve the grand narrative. Instead, I would create a universe of moral paradoxes in which alien races would invade Earth and threaten the so-called human value system—nationality, identity, gender, and even the concept of “time”. In this case, aliens who are perceived as obscene and erotic could lead to the extinction of human values. One of the main concepts of this new narrative comes from Jack Halberstam’s “Queer Time”, as a lever, it will influence and reorganize a chain of thoughts in my concept, including relocation, reset, anti-production, anti-”capitalist’s time”, anti-male and classical view of history. Furthermore, it may thus open up the scope of the concept of queerness to include a variety of sexualities and ethnicities. To Fuck the Time, as a metaphor and a resistance.

1972, Toffler

Multi channel installation, 2023

In recent years, Su has employed the approach of “re-shooting” as his method to create new works, which revisit past, unfinished, tabooed, and misunderstood figures, events, and things. Through his work, he is able to achieve new revelations or unveil active historical viewpoints. Sing Song-Yong, the researcher of the exhibition, thus comments on Su’s work in his essay written for the exhibition: “The key to the uniqueness of Su Hui-Yu’s work, in my opinion, lies undoubtedly in the fact that he acutely captures potential meanings of past cultural events in relation to his own generation, through which his works become bold statements about what has not been expressed in the past.” After being re-interpreted by Su and through his lens, a new life of controversial or seldom discussed works from past eras emerges.

The title of the exhibition is inspired by American futurologist Alvin Toffler’s book, Future Shock (1970), which was translated into Mandarin and published in 1972. In Su’s homonymous work, Future Shock of 2019, he utilizes the approach of re-shooting to re-interpret Toffler’s masterpiece, from which he applies keywords from new terms and notions proposed by Toffler to the narrative. Three years later, Su presents his latest work, Toffler, Oliver, and the Last Man on Earth, which continues the creative concept of re-shooting. However, different from the previous work that has a narrative based on chapters, the video work in 1972, Toffler is divided into several frames, combined with photographic works and sketches, which are shown in two gallery rooms. The images of the video show an endless road trip of the last survivor on Earth, accompanied by Oliver, a smart computer from the original book, invented as an aid to humanity. The labyrinthian style of visual expression prompts the audience to piece together the otherwise fragmented images by themselves, allowing them to choose their own viewing angle to approach and understand the work.

Revenge Scenes

Performance/mobile devices interaction/live-streaming, 2021

Revenge Scenes by artists Su Hui-Yu and Cheng Hsien-Yu can be considered as a live art and installation work developed from Su’s earlier work,The Women’s Revenge. The work utilizes live streaming, augmented reality, and machine learning among other techniques, to lead the audience back into the history of social realism films and (female) exploitation films in the 1980s, where it highlights the ambiguous similarities between social media culture and exploitation films through the juxtaposition of the two. The work depicts the contemporary media society’s portrayal of the body and further questions the issue of body politics under new media technology. Revenge Scenes features live performances with augmented reality elements. Through the audience’s assistance in broadcasting, the images are shared on social media platforms and other locations where the videos are redeployed in real-time.

In its passive exhibition form, Revenge Scenes is transformed into the form of a crime scene instead of its performance version, where it continuously raises various questions about our history and future, such as:

How long or how heavily have humans desired or depended on contents being “live”? Since the dawn of imaging technology, how have “messages” collaborated (or challenged) with reality? What is the current state of “mediatization” of our bodies? How else can we train our bodies? Under the assistance and influence of contemporary technology, can we further ease the tension and predicament in issues as gender, sex, and physical body (even soul)?

Following on the reasoning above, if we further question our body, after this transitional process involving body/signal, linear/non-linear, analog/codes, and followed by the targeted placement and manipulation at the end of the process; where will this finally lead us (and our desires) to? Can a future “technique of desire” be expected? Can this be a calculated spiritual transcendence, or become yet another self-surveillance, exposure, and betrayal of The Transparency Society?

The White Waters

Multi-channel installation/live art, 2019/2020.

“Critical Point Theater Phenomenon” was established in the late 1980s by TIAN Chi-Yuan and others.As the first publicly documented college student with AIDS, TIAN and Critical Point not only launched a new era of experimental theater in Taiwan, but also represented a significant moment in the history of gay culture. In 1993, Critical Point presented its seminal work, “White Water”—a contemporary reinterpretation of “The Flooding of Jinshan Temple” episode in The Legend of the White Snake, which explored themes of homosexuality, love, and political identity; and touched conceptually on the domain of the post-human and anti-anthropocentrism.

The White Waters uses TIAN’s classic as leverage in a return to the classic legend. The work focuses on imagery such as flood/fluidity, violence, sex, gender, illness/death, post-human, and antianthropocentrism, etc., so as to contemplate the numerous thoughts and fissures in both The Legend of the White Snake and“White Water,” hence enabling the cognitive structures of desire, life, morality, and identity to be laid bare once more. In form, the work utilizes colors to create structurally distinct segments, and showcases the artist’s many flights of fantasy regarding the above. The performance on video has been enacted by Instagram sensation JONG Yi-Ling and Popcorn, an active participant in Taipei’s drag community.

The Women’s Revenge

Multi-channel installation, 2020.

Prior to Taiwan’s lifting of martial law, a group of films influenced by the European wave of exploitation movie was produced in the 1980s, including Never Too Late to Repent, Woman of Wrath, On The Social File of Shanghai, Woman Revenger and Queen Bee. This filmic genre featuring the motif of “women’s revenge” would usually portray some severely oppressed heroines before culminating in bloody plots of vengeance. In continuation of Su’s creative context of “re-shooting” in recent years, The Women’s Revenge uses Taiwanese exploitation movies as a starting point to reexamines the problems of body regulation, seeking social novelty, modern discomforts and mediatized body. It also discusses how plots based on feminism have been turned into exploitation movies, reflects on the misunderstanding and exploitation of female sexuality in the system of image, and exposes how the contemporary body is manipulated by image technologies.

For the artist, these films point to a blackhole in history, in which a mixed bunch of images devours possible clues to explore the life politics of an entire generation. Formally speaking, the artist also takes part in the violent vengeance upon men by transforming himself into one of the avenging women – the box office guarantee for the 1980s Taiwanese cinema and the Best Leading Actress of the 20th Golden Horse Awards, Lu Shao-Fen, with a peculiarly proportioned body – through makeup and the technology of deepfake. The transformation also symbolizes an attempt to understand and experience women’s world with a man’s body.

Future Shock

Three channel installation, 20’00”, 2019.

In 1970, futurist Alvin Toffler’s iconic work Future Shock was published. One year later, a translation hit the market in Taiwan, thus introducing the writer’s theories to readers of Chinese. The premise of the book can be summed up as: “A future that comes too quickly creates more apprehension than that of a foreign land. Future society will be stricken with a plethora of choices, throw-away society, information overload, and unethical technology.” The video work was inspired by Toffler’s original, from which the artist adapted and developed Toffler’s theories. The artist decided to shoot the film in the southern city of Kaohsiung for its industrial facilities, modernist architecture, power plants, commercial institutions, and deserted amusement parks, which were driven by economic policies in the 1970s, but today evoke feelings of strangeness and nostalgia for the city’s golden age. This past which felt so futuristic 50 years ago is now both confusing and familiar. Future Shock leads audience members to revisit retro Kaohsiung from a contemporary perspective and look back as if in a dream at the influence of “modern” and “future” when they were completely new concepts in Asia.

The Glamorous Boys of Tang (Chui Kang-Chien’s,1985)

Four channel installation, 17’00”, 2018.

In 1985, two years before the end of Taiwan’s martial law period, the renowned poet and screenwriter Chui Kang-Chien’s (邱剛健) Tang Chao Chi Li Nan (trans: The Glamorous Boys of Tang) was first screened in Taiwan. The film is a homoerotic fantasy, and was therefore not well received due to the conservative atmosphere at the time. The film’s first scene is an inexplicable exorcism ceremony which includes dancing. Next, two pretty boys appear, and when their eyes meet, the scene is suffused with their mutual fascination. The plot also includes disturbing killings, death, and orgies accompanied by dissonant sound effects made with a synthesizer, bizarre and gaudy set design, and ill considered costumes. The combined effect is something like a cult film. Comparing the film to the script held in the Taiwan Film Institute archives, it is obvious that the film has been heavily edited or many sequences could not be depicted in detail. Perhaps the filmmakers could not fully present the radicalism and passion of the screenplay due to budget restrictions, censorship, or marketing concerns. More than thirty years later, with new funding and film technology, Su Huiyu has re-created the film to call together the differently gendered bodies and subcultures of Taiwan’s diverse society. The four channel piece can be seen as a re-shooting, a re-narration of the original 1985 version, or the next leg of its journey.

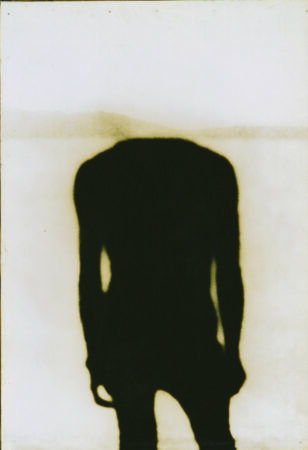

L’être et le Néant (1962, Chang Chao-Tang)

Single channel video, 5’00” loop, 2016.

This work is an attempt to reassemble(not interpret) Chang Chao-Tang’s famous photo piece Being I (the translation of Chinese title is supposed to be Being and Nothingness). The atmosphere of 1962 was darkened by the shadow of martial law and the White Terror. It was an era when people’s thoughts and the feelings had nowhere to go. This sense of stifling and emptiness happened to resonate a little in tone with existentialism, the prevailing “trend in the world thought” at the time. While this resonance had very little to do with comprehension, and may have even been little more than a similarity in title (Jean-Paul Sartre had published his book Being and Nothingness in 1943), it still precisely captured the zeitgeist – a marginal zone of longing for freedom that was unattainable, longing for truth that lay out of reach. Today when revisit the scene of Chang’s Being I, we can’t help being abruptly shocked. That experience of being suffocated, being incarcerated, that sense of being tightly constrained or even a little terrified seems not so far away.

#1960s #Being_and_Nothingness #White_Terror

Nue Quan

Duo-channel installation, 8’00”, 2015.

Ne Quan was inspired by a boxed-corpse murder case that happened in 2001, Taipei. Two men who met online went out for an erotic asphyxiation experience which resulted in death of one of the man. The body was abandoned and all traces were obliterated. Since this murder involved homosexual, online sex, SM and body of a man abandoned in a suitcase, the media had depicted it with a mysterious and dramatic perspective. The suspect, with his online nickname as Ne Quan, was heavily criticized by the society and the general public. The Ne Quan murder case reminds Su of dreams where he was involved in murder. Abandoning the corpse became a direct reaction following the sense of guilt in his dreams. This work has recreated the illusionized murder scene, by combining the artist’s personal dream and the murder from the news, to make the audience reflect on sex, self and moral justice in the modern society.

#Homosexual #Mass-media #Sadomasochism #Nightmare

Super Taboo

Duo-channel installation, 18’00”, 2015.

Adapted from historical texts, the narrative in the two-channel video artwork Super Taboo came from a pornographic publication, which was previously known as “a small book”, with the same title. In addition to illegal copies of pornographic photos from Japan and Western countries, the undisguised description of erotic scenes is now a mesmerizing vernacular Chinese literature. In this video, the renowned actor Chin Shih-Chieh(⾦⼠傑) guides the viewers into a surreal erotic scene by playing the role of an urban white-collar worker who mutters the plots of the “small book” in his hands. The work leads us back to the 1980s Taiwan. Pornographic content was then edged to the periphery of the audio-visual system and merely tolerated by late night shows, secret rooms in video rental shops, or inconspicuous corners in bookstores. However, banned pornographic content tended to put greater erogenous temptation in our way than that freely accessible to us did. Pornographic content holds its allure at the expense of being salacious, nasty, and immoral. Physically pleasant sensation seems to be perilous and ergo requires the endorsement by the transcendental love or a social context as the foundation.

#Pornography #Forbidden #1980s